Why would I buy it when I can right click and save as?

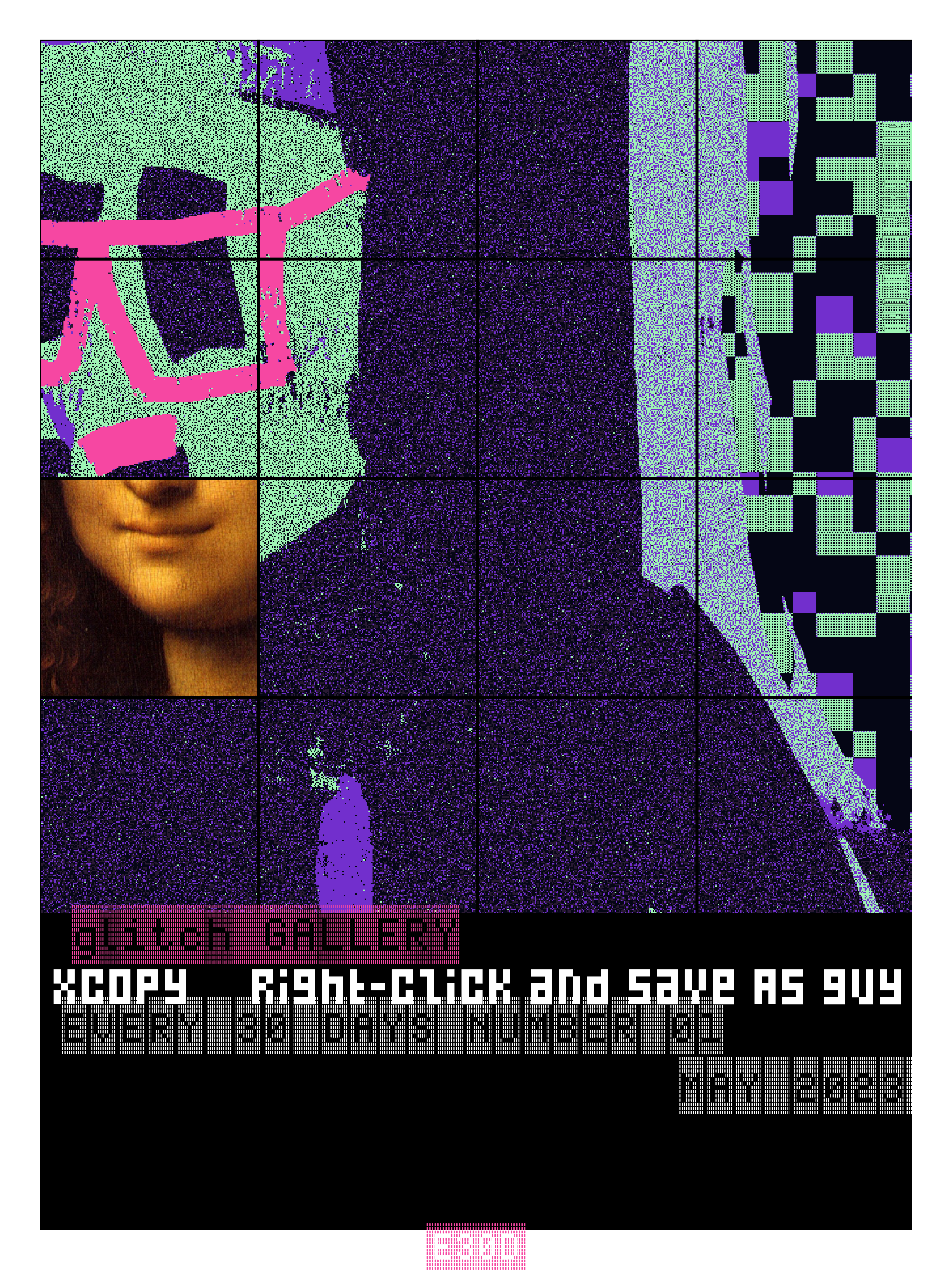

These thirteen words act as the sole description of XCOPY’s most iconic digital artwork, minted on December 6th, 2018.

Like few other works, “Right-click and Save As guy” captures an antiquated prejudice against digital art objects — computer files anyone can “own” by saving them with a mouse click. The work represented a shift toward what the world deemed previously impossible — the ability to imbue a digital object with scarcity.

Changes in technology, especially technologies of reproduction, have always affected the shape of art and its socio-economic significance.

When photography and cinematography began to demonstrate widespread influence in the early 20th century, critic Walter Benjamin noted that the “…work of art becomes a creation with entirely new functions.”1 In a similar vein, non-fungible tokens on decentralized blockchains change the objecthood of digital art. Through the ERC-721 token standard, digital artworks turned into unique, persistent objects that can accrue value: an essential shift in what it means to be an art object in the digital realm.

Part of the cultural significance of “Right-click and Save As guy” is, of course, its prognostic power. At the dawn of crypto art, the work anticipates the shift from a technical possibility to a cultural reality. When this shift occurred, the parabolic cultural and economic success of the work – which skyrocketed from 1 ETH in December 2018 ($90) to 1600 ETH ($7M) three years later – confirmed its genre-defining status.

Developments like this are not unprecedented in the history of art. But the speed of which it occurred most certainly is. In less than three years, XCOPY’s “Right-click and Save As guy” defined the very category of a unique digital art object, and this is why glitch chose this work to premier the Every 30 Days exhibition. “Right-click and Save As guy” is an artistic proof of concept for digital ownership, and an important symbol of our movement.

The anonymous XCOPY uniquely positioned themselves to take full advantage of this cultural shift. In the decade before their first sale, the artist developed a distinct visual vocabulary and established a cult following by posting their art (for free) on Tumblr, a microblogging social network founded in the early 2010s. As venture investor and crypto art collector Derek Edwards argues, the value of digital objects is tied to their capacity to be “networked with attention.”2 The audience that XCOPY built on web2 rails created the foundation for success they would later enjoy in web3.

Importantly, XCOPY detaches ownership of the digital object from the legal layer. All copyright of his digital work has been relinquished and dedicated to the public domain (CC0). This mechanic invites the artist’s audience — not just owners of his work — to spread, cite and remix the work over time.

One might assume that CC0 mechanics dilute the influence of artwork at hand – but this could not be further from reality. In the age of the internet, CC0 designations have a unique ability to expand the invisible networks around a digital object. Ownership over a digital object must be provably scarce. But non-original derivatives of a digital object are no longer enemies of the original; they are the transmission and distribution vehicle for a global audience. In the world of blockchain-authenticated digital objects, the contested modern notions of “original” and “copy” no longer stand in a competitive relationship. They are complimentary. XCOPY’s work is an iconic commentary about these shifting nuances in the meaning of originality, value, and uniqueness in a new digital era.

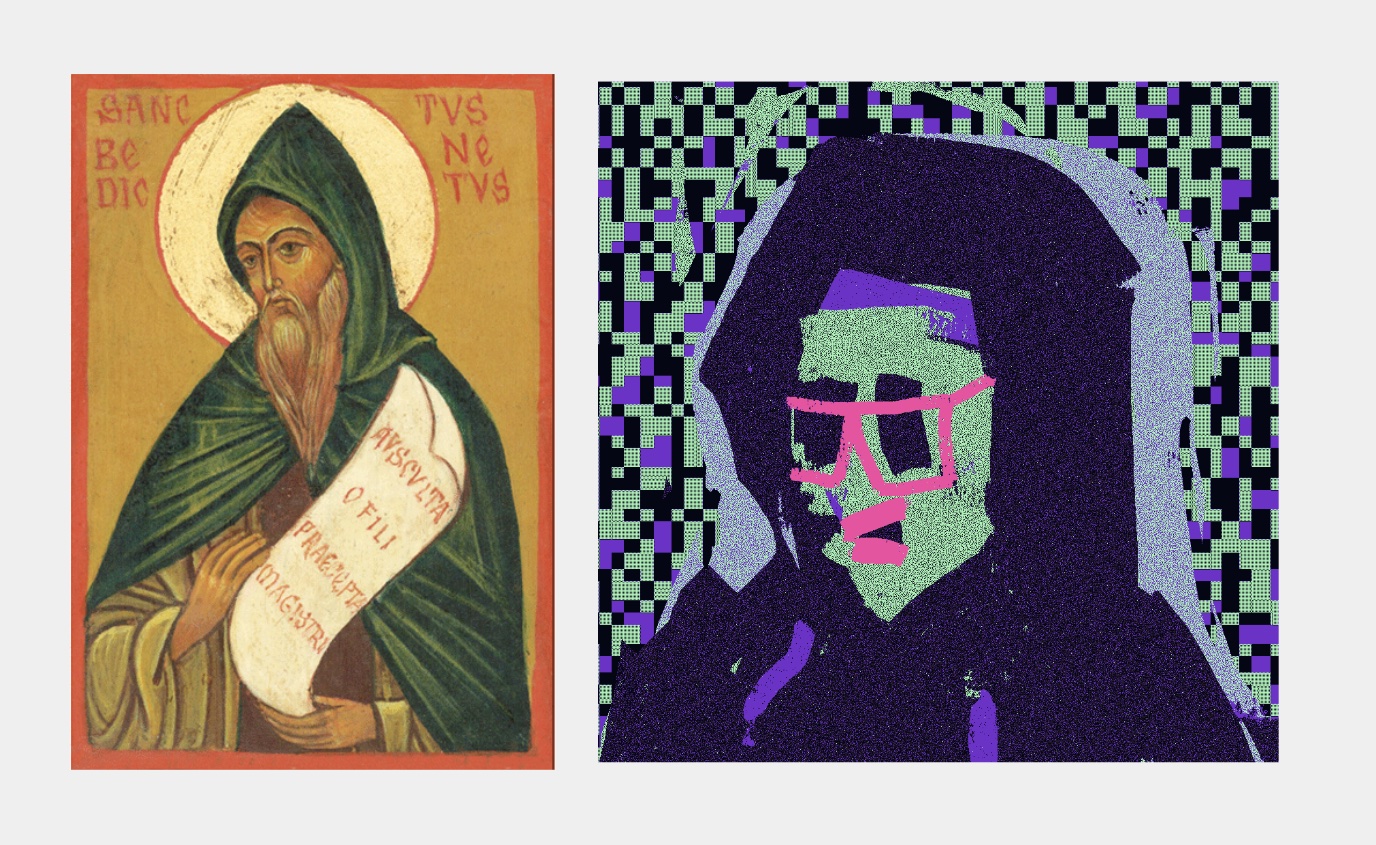

“Right-click and Save As guy” is not only iconic in the metaphorical sense in that it defines an era. The adjective “iconic” derives from the Greek “eíkōn,” meaning likeness, image, pattern, and archetype. The category that has become mostly closely associated with the term are the portraits of saints in Byzantine art.

And, whether intentionally or not, “Right-click and Save As guy” bears a striking resemblance to this aesthetic. With the figure’s gaze cast down and its face framed by a hoodie that resembles a dark hollow, the portrait feels like a contemporary version of an iconic portrait. Other works by the artist—“Jesus Mob” and “Saint Less,” in particular—make it likely that this reference to Christian iconography is indeed intentional.

But what makes icons special? And why do we call significant works of art “iconic” in the sense of something notable, recognizable, memorable, or popular?

Before the modern concept of art was born in the Renaissance, icons were objects of veneration to which people attributed a certain “agency.”3 Similar to memes in 21st century internet culture, icons spread through a viral network logic. They traveled across physical borders and language barriers in the age before the printing press introduced mechanical reproduction for texts. The portrait form has retained its remarkable power since then, capable of capturing moments of cultural significance in a single image. It is no coincidence that the most famous painting in the world, the Mona Lisa, is a portrait.

And just think of how Andy Warhol’s iconic pop art portraits capture the atmosphere of the 1960s. From this perspective, it is quite consistent that the paradigmatic digital art object, whose value stems from its capacity to be “networked with attention,” would take the form of an iconic portrait.

“Right-click and Save As guy” updates the iconic portrait form with a unique glitch aesthetic. A pixelated face, flickering pixels in the background, heavily saturated colors, and moving pink lips lend the image the sense of distortion so characteristic of XCOPY’s style. There is an intensity in the artist’s work that makes it seem as if the surface of the screen has been scratched open to excavate the base layer of raw pixels. Yet this visual violence balances easily with the recognizable portrait form.

It is, perhaps, precisely this carefully curated clash between the classic format of the portrait and the flashing glitchcore chaos that gives XCOPY’s work its mesmerizing force. A similar montage is at play in XCOPY’s thematization of entropy, death and decay. Allusions to meaninglessness in contemporary consumer society abound in their work, and they are often blended with the allegorical themes of memento mori, danse macabre and vanity.

In the images that captivate us, there is often more than meets the eye. XCOPY’s work in particular is rich with themes that the artist both evokes and erases (appropriately enough, their work “ART HISTORY: VOLUMES I-X” shows an open book with burning pages). The figures in the artist’s world are dark, apathetic, but never too serious. They appear as happy nihilists, cognizant that death will have its day, yet still joyfully embracing the memes of crypto culture – making “Right-click and Save As guy” something like the patron saint for the collectors of digital objects.

-

Walter Benjamin, The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility and Other Writings on Media (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008), 26. ↩

-

Derek Edwards, “Storing Value in Digital Objects” ↩

-

Hans Belting, Likeness and Presence: A History of the Image before the Era of Art (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1993). ↩

.gif)