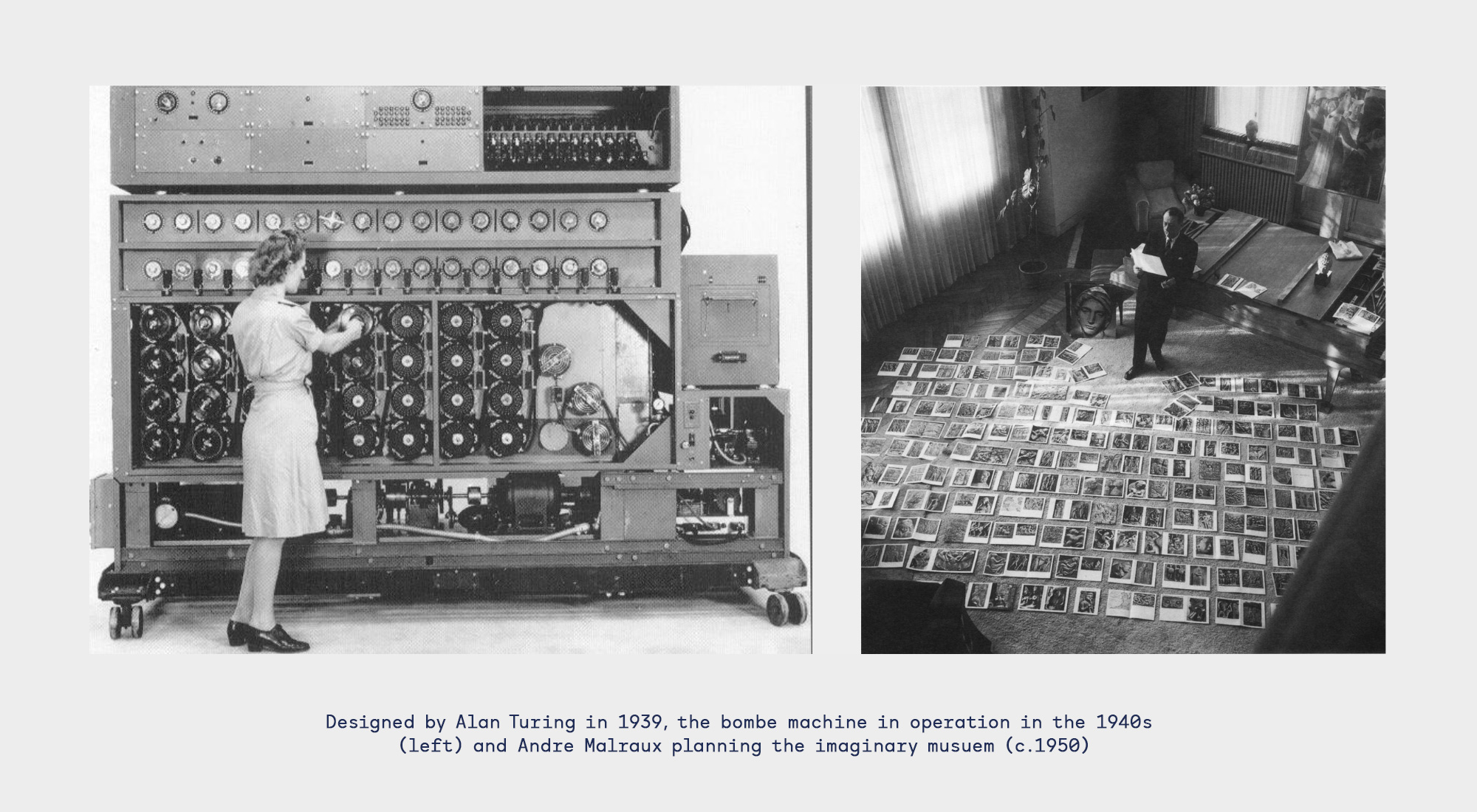

More than 70 years ago, Alan Turing first posed the simple question, “Can machines think?” 1

Few would doubt that the development of computation in the last decades has led ever closer to an affirmative answer. When speculating about future progress in artificial intelligence, even Turing confined himself to the thesis that “machines will eventually compete with men in all purely intellectual fields.” 2 Purely intellectual fields refer to calculation and logical inference, whereas human creativity is often imagined to operate in a vastly different realm, an idea that still persists today.

So, what is genuine creativity? Usually, it is understood as creating the radically new, incommensurable, heretofore unseen. However, the notion of radical innovation, of an original and unprecedented creation, is a dubious leftover from the Renaissance cult of the artist, in which the language of divine creation became entangled with that of artistic skill. 3

Nothing comes from nothing. Everything references something. Culture is never, bang-bang, emergence from the void. It has always been a kind of bricolage. In the domain of fashion, the cyclical reinvention of trends illuminates this concept; “new” styles are created by revisiting and updating past styles. Walter Benjamin captures this paradox, noting that fashion “has a flair for the topical, no matter where it stirs in the thickets of long ago.” Beyond the fashion sphere, this pattern prevails across all cultural fields to different degrees, which continuously remix and repurpose existing elements to form new constellations.

In other words, culture is based on the principle of remixing. And it is no coincidence that the most ancient notion of art has its origin in the Greek “tékhnē,” the concept of technology.

By definition, art is and has always been in dialogue with technology.

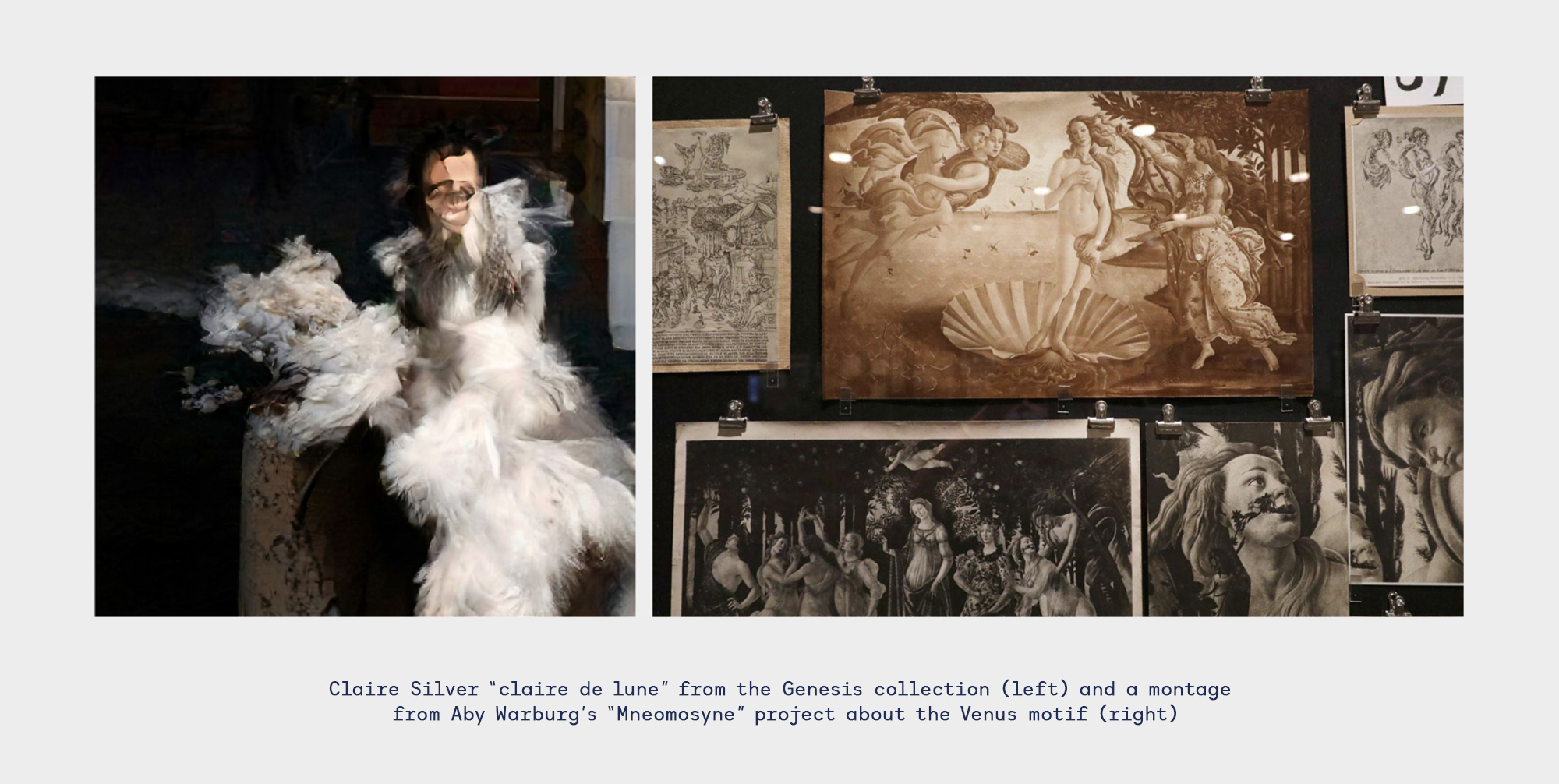

Claire Silver, an AI artist who prefers to remain anonymous, proclaims in her Twitter bio: “Taste is the new skill.” This by now often-commented statement seems self-evident: digital technology has enabled access to creative tools on a scale previously unimagined, a trend that has been catalyzed further by the recent advent of various generative AI tools. After these tools have leveled the playing field for creatives, it is style (rather than technical proficiency) that becomes the ultimate metric of artistic merit.

Nevertheless, there is a deeper implication at play in Claire’s motto, one that brings to the fore the very nature of creation and the relationship between artists and their art.

As the landscape of AI artists continues to expand, Claire Silver stands out for her articulation of the innovative approach to creation. Defining herself as a “collaborative” artist, she frames her work with generative AI as a partnership, setting it apart from the common perception of AI as a mere instrument or tool. In Claire’s practice, the interaction with AI generators resembles a conversation rather than simple means-end-relationship.

As a result, her work introduces a novel type of the 21st-century artist: engaging in co-creation as opposed to singular innovation, prioritizing taste and curation over proficiency understood in the narrow sense as inherited craftsmanship, fostering open dialogue instead of inscrutable opacity, and embracing anonymity over idealized personality cults. In these ways, Silver gives rise to a distinct visual poetry, rich with references to art history and meta-commentary about AI art.

In the period when Turing established the principles of artificial intelligence, art historians were developing photographic analog models anticipating our current image generation tools. The proliferation of illustrated art books, facilitated by the progress of photography, liberated visual artifacts from geographical and chronological constraints for the first time. In a period when experiencing art no longer requires physical presence, these works could cross boundaries and form new connections. André Malraux explored the idea of an “imaginary museum” without physical borders, denoting the possibility of assembling and juxtaposing every artwork that had ever been photographed.

During the 1920s, art historian Aby Warburg engaged in an examination of the unfolding of visual motifs and patterns over time, utilizing photographic plates to track the emergence of specific themes. Warburg traced something like a collective visual subconsciousness and dubbed his project after “Mnemosyne,” the Greek goddess of memory and mother of the muses: that is, of inspiration itself.

While Malraux’s “imaginary museum” and Warburg’s “Mnemosyne” project explored the idea of juxtaposing various data points from cultural history, AI image tools allow users to synthesize the entirety of cultural history to new visual objects. After photography has made the history of visual artifacts available as an archive, AI tools transform this archive into an extended power of imagination. In the history of images, this possibility of co-creation—or “collaboration,” in Claire’s terminology—is on par with, or may even exceed, the “liberation“ of artworks through photography. Regardless of artists employing self-trained data or utilizing diffusion models, the breakthrough of image generators is marked by the ability to establish semantic relationships between visual components. Nothing has ever come as close as these models to a collective visual subconsciousness.

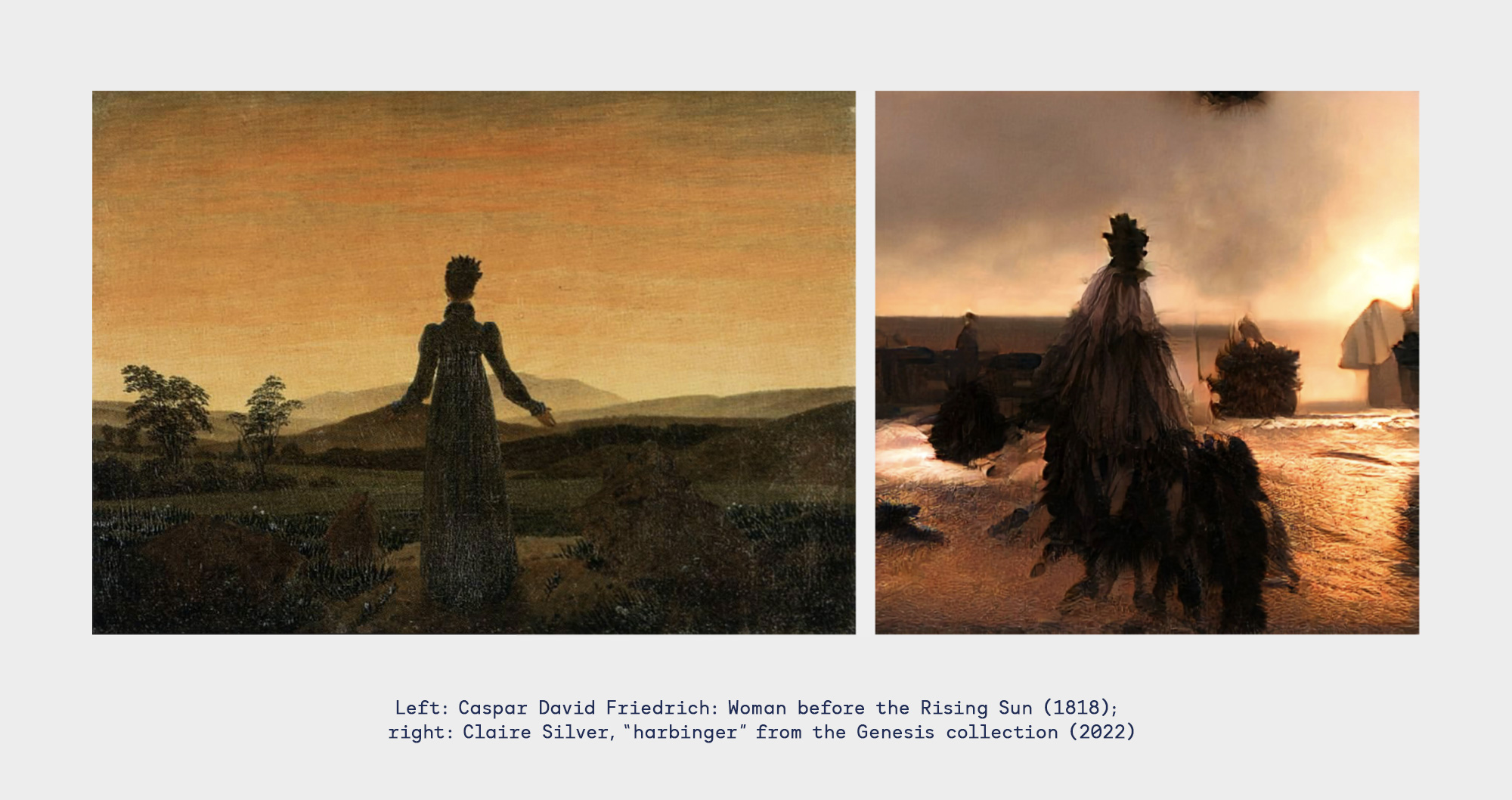

Silver’s “Genesis” project encompasses 500 uniquely titled outputs. Minted on the first day of the Braindrops AI platform launch in April 2022, the output space is organized through narrative-guiding attributes. The “chapters” trait comprises categories such as “transcendence,” “crossroads,” and “relics of aristocracy.” The “cycle” trait features “nocturne,” “daybreak,” and “sunlight,” while the “descriptive” trait classifies images with labels like “garden,” “architecture,” “ghosts of future past,” and “android.” The images exhibit a dark and opaque atmosphere, imbued with a unifying poetic quality that encourages viewers to envision diverse narratives while perusing the collection.

Viewers familiar with painting history may encounter a persistent déjà vu, as numerous outputs evoke familiar compositions, lighting arrangements, and motifs. These images employ a visual language that subtly echoes patterns recognizable to the viewer. Yet, these echoes remain intangible, they do not reference any work in particular.

Viewed collectively, “Genesis” presents itself as a cryptic assemblage of allusions and narrative fragments, akin to pages from a once-cohesive book now rendered indecipherable.

The selected output for the current exhibition at glitch — titled “bug” and owned by the premier decentralized collecting group Flamingo DAO – belongs to the “daybreak” chapter and features an “exterior” locale. It depicts two white figures set against what seems to be a mountain range with a structure or wall in the foreground. Do the white garments signify religious attire? Are the figures convening at daybreak for a ritual? Are they departing the city for work? The image’s semi-figurative and semi-narrative nature both invites and defies interpretation, partly due to the visual language’s inherent indeterminacy.

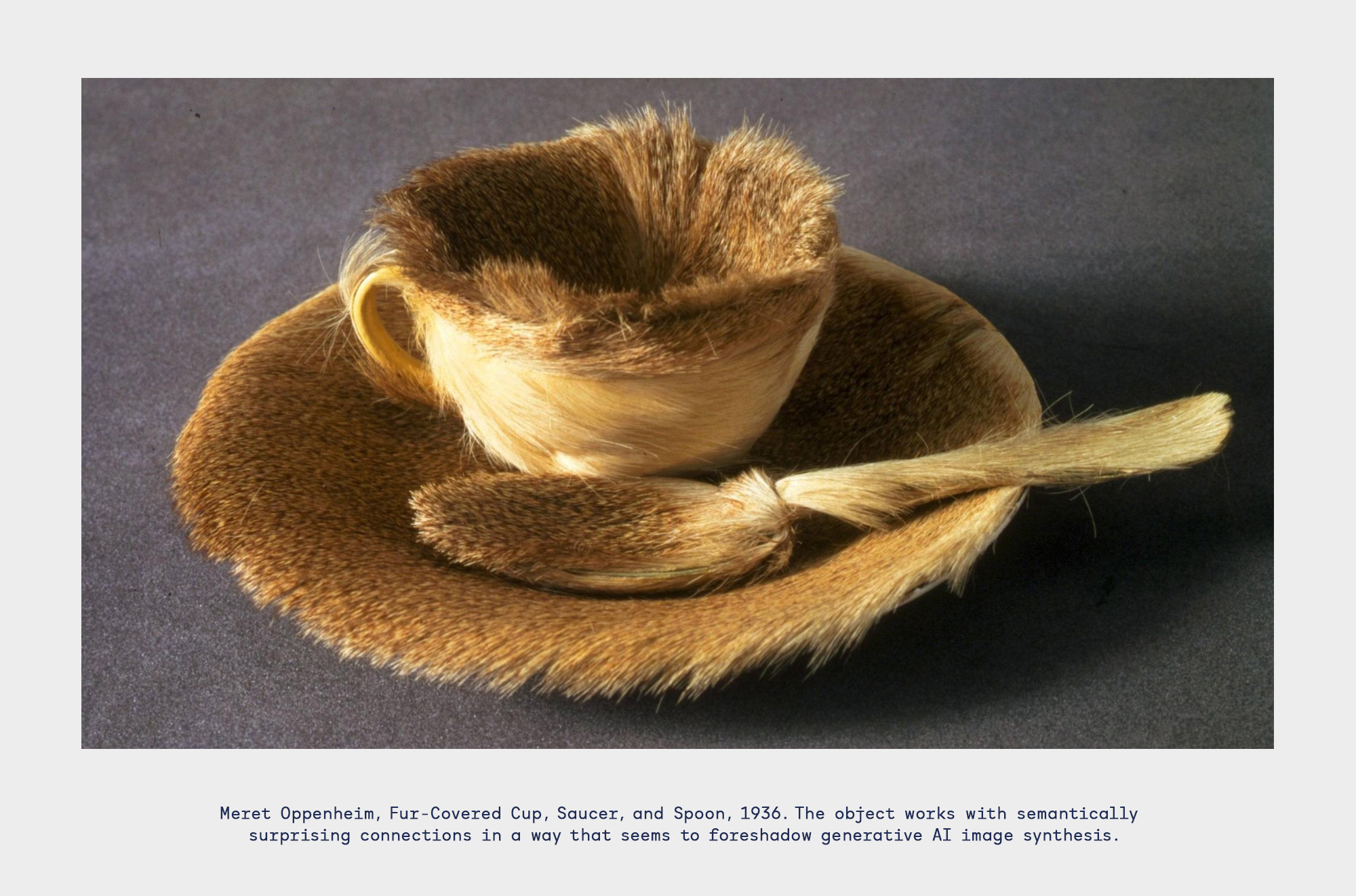

The figures appear slightly distorted and blurry, while the semantic connections between the visual elements are discernible. This peculiarity often leads observers to describe the AI generated images as “surreal.” The surreal, like the uncanny, embodies the extraordinary within the familiar. The semantic relationships forged between various visual elements by AI models from over a year ago approach our perception without truly attaining it, resulting in the distinctive distortions and formlessness. It is not the extraordinary, but rather the subtly altered ordinary that evokes the most eerie and mysterious sensations, and it is precisely this effect to which Silver’s work lends a poetic nuance.

Digital art collectors, particularly those focused on on-chain generative art, were ideally situated to comprehend this type of “long-form” AI art. Both on-chain generative art and AI art can be encompassed under the “generative” art umbrella, with both forms relying on randomness and emergence. However, the specific nature of their random components diverges. On-chain generative art operates within a deterministic framework, where certain attributes possess specific probabilities. Randomness is defined as an arbitrarily deterministic event with a pre-specified probability distribution, and the token hash used as input generates a random output from this probability. The same token will consistently determine the same output. In contrast, AI art may produce different outcomes from the same output at varying times. With regard to Silver’s work, this means that the process of defining attributes is an ex-post form of manual curation and story-telling rather than defining probabilistic traits.

The digital realm has always been defined by the principle of abundance, as marginal costs approach zero. Both generative and AI art employ content creation processes that align with this abundance principle. AI tools, in particular, are set to accelerate task automation and cost reduction significantly in the years to come.4 As such, they minimize the marginal costs of creative production, potentially leading to content inflation on an unprecedented scale.

Instead of undermining scarcity, however, this new reality will accelerate the adoption of blockchain-based databases: digital environments that can establish property rights for unique digital objects — regardless of whether these objects are created by machines, humans, or in partnership between the two.

-

Alan Turing, “Computing Machinery and Intelligence,” Mind, Vol. LIX, No. 236 (October 1950): pp. 433–460; p. 433. ↩

-

Ibid., p. 460. Our italics. ↩

-

Patricia Emison, Creating the “Divine” Artist: From Dante to Michelangelo (Leiden: Brill, 2004) ↩

-

See Joseph Briggs et al., “The Potentially Large Effects of Artificial Intelligence on Economic Growth,” Goldman Sachs Economic Research (March, 2023). ↩

.png)